One of the attractions of having a website is that it operates twenty four hours a day, 365 days a year. However, depending on what your market is, it might not operate evenly on all of those days. The phenomenon of market seasonality is well-understood in offline businesses — ice cream shops do most business in the summer, retailers have a 4th quarterly sales spike — but understanding of it seems to be fairly limited among software companies. Since market seasonality has non-trivial impact on many software businesses, I thought I would write about what I’ve learned.

Brief Background

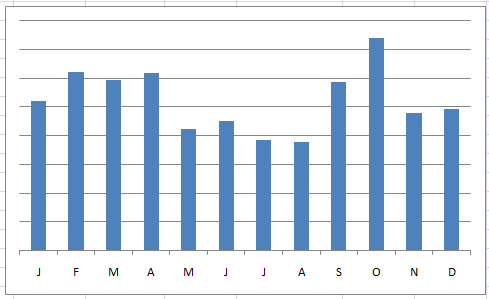

I sell software which makes bingo cards to elementary schoolteachers, who overwhelmingly purchase the software with their own money directly in advance of the day they plan to use it. This gives me a very quirky calendar relative to many software businesses. Collapsing my sales chart for the last several years over the calendar year produces…

As you can see, I have a trough of sales every summer and a spike in October, among other seasonal anomalies. More about why that is later. This is just the sales graph, but almost any other statistic for my business — page views, signups, ad impressions, search traffic, etc etc — more or less tracks this curve, although that isn’t going to be the case for all businesses.

Know Your Market

I came into this situation more or less blind: prior to starting my business, if I had thought about it, I would have expected “Yeah, sales are probably going to pick up when the school year starts”, but the huge spike in October and the mini-trough in November/December were all surprises to me. If possible, don’t be surprised. Presumably you are expert or near-expert at your particular problem domain, and should be accustomed to what your business calendar probably looks like in your market. If you aren’t, time to make a courtesy call to either customers or competitors and ask them. (Sure, you can ask your competitors this. Why not? If you’re worried about being laughed off the phone, then find someone who is publicly traded and look at their quarterly earning reports. The numbers and explanatory notes will often give you all the information you need.)

For highly seasonal businesses, get used to the words year-over-year. As in, sales in July for me were up 42% year-over-year, meaning that they were up 42% as compared to last July, as opposed to comparing them with this June. This gives you a much more accurate picture of where the business is going, because for businesses which are not growing at truly meteoric rates, seasonal effects can very easily swamp the underlying trend. (If you’re a viral Silicon Valley darling, you may be able to discount this. However, if you’re a retailer, it is virtually impossible to have a January better than your December. In fact, if it happens, it means you probably had a catastrophe.)

Cash Flow Management For The Off-Season

When people stop buying what you sell, you’ll tend to have less money. That sounds vacuous, but it has important implications for your cash management. It means that you’ll need to model your behavior on the ant, not the grasshopper: when times are easy, save up for when times are going to be difficult.

There are other options besides just banking money made during the on-season. For many businesses, support loads, marketing activities, and the like all roughly coincide with the level of sales. The number of emails I send regarding Bingo Card Creator falls by roughly 80% during the summer months. This frees up a lot of time and focus in your organization. One option to keep the lights on for software businesses is to do consulting or similar billable work during the off-season and go back to the product during the on-season — I took advantage of that this summer, to avoid breaking the piggybank too badly.

Another option, very popular among offline businesses but not used much online, is to do seasonal sales. For example, if you sell software to teachers, you could do a back to school sale in August and, essentially, cut three weeks off of summer. I did a 20% discount one year from late July through mid-August, which helped cushion the blow a bit.

Many SaaS startups are currently scratching their heads wondering “Why does this matter?”, because they get consistent revenue on a monthly basis regardless of when the customer’s signup was, and hence can’t conceive of having a growing user population and falling revenues. This is yet another enviable reason to sell software on a subscription basis.

Other Ways To Exploit The Off Season

If you find that your marketing, customer support, and what have you decline in the off season, and you don’t need to find someone to bill to keep the lights on, you have a variety of fun options:

- Deploying new features, particularly ones which involve significant engineering changes (like wholescale site redesigns or business model changes), gets much easier when 80% of the user population is not actually on the site. In the event you have an issue, the number of people affected by it is likely to be much smaller, and you’ll have a few months to get the kinks out prior to sales hitting their peaks again. When I released the online version of my software last year, conversion rates plunged by about 30% while I was getting debugging the software and (more importantly, as it turns out) the marketing message. Since it was the dog days of summer, though, that didn’t end up costing me all that much money (although it was a sock in the gut to have my first year-over-year decline ever).

- For similar reasons, there is never a time like the present to start on a new project. It might be worth doing one which either has a different seasonal cycle, or none at all, as this eliminates the cash flow challenge. (On the other hand, having a built-in 3 month vacation isn’t the worst problem in the world.)

Communicating Seasonal Effects

To the extent that outside parties do not understand the seasonality in your market, you need to educate them. Investors, for example, might assume if they come from a non-seasonal background that any dip in the “up and to the right” story means you are losing traction. It is a virtual certainty, for example, that GroupOn is going to sell less coupons in January than they will in December. Having an article on TechCrunch saying “Groupon Growth Finally Puttering Out?” would not be positive for them (well, to the extent that TechCrunch coverage matters to a profitable business…).

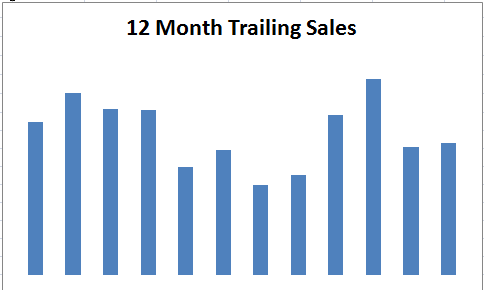

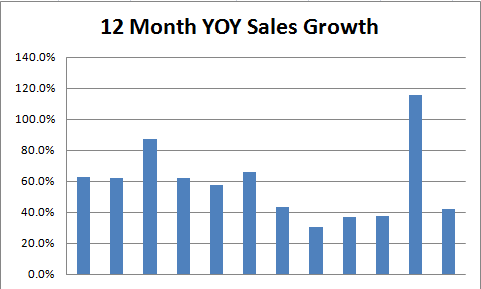

Here are two very different graphs:

And here’s the same data, presented in another light:

The first business looks like it has had mostly flat sales for the last year, and a recent slump. The second business looks like it is killing it. They are the same business. In the rather unlikely scenario that I was seeking investors, I know which of these two graphs I’d put in my slide deck.

Other presentational techniques to use:

- Second derivative of (pick a metric: sales, signups, etc). The story is “We’re growing faster all the time.” (Note as you can tell from eyeballing the above graph this is not actually true for me.)

- Pick a metric where the seasonal effects are less apparent. Conversion rates are wonderful for this, since often you’ll have an increased conversion during the off-season. (If someone comes into an ice cream shop in December, that is because they really, seriously are in the mood to buy ice cream. They’ll also find the place absolutely deserted.)

Plan In Advance For Peak Season, Too

The top of the year for educational bingo is in October, due to a massive influx of teachers wanting to play Halloween bingo at their class party. (A brief aside: Halloween is considered a holiday of special importance to young children in America, but they aren’t given the day off, which means teachers want to do a fun activity in class to commemorate it. It has also been mostly secularized, which means public schoolteachers are at no risk to their career if they throw a Halloween party, whereas throwing an Easter party is a wee bit tricky. You have to do it without mentioning Jesus and, simultaneously, without mentioning that you’re not mentioning Jesus. Most teachers just have a chocobunny and hope for break to arrive.)

When I was young and stupid, I started planning for Halloween in October. That works very poorly for Internet marketing: it will take months for your holiday-specific content (such as my page about Halloween bingo cards) to start ranking in the search engines where you want it to be. If you do AdWords advertising, starting a campaign right before a holiday is likely going to be disastrous, because a) if it gets plunged into approval purgatory you just missed your holiday (this has happened to me quite frequently) and b) your campaign won’t have time to build up the positive history which will get it the widest exposure and best costs.

For SEO projects, start several months in advance of holiday or season you’re targeting. For AdWords, I’d recommend at least a few weeks. These schedules can be attenuated if you have a national-level brand to fall back on or a built-in tribe of evangelists like 37Signals has assiduously cultivated, but in general, more time is better. (If this sounds like a whole lot of work, that is only because it is a whole lot of work, but you can have stupendously disproportionate returns to seasonal promotions. I set records every year at Halloween even without ranking #1 for the term I was most interested in, and now that I am ranking #1 I am cautiously optimistic that I’ll absolutely smash my records this year.)

If you have another facet of this you’d like covered, or if you have some tactics which have worked for you, I’d love to hear about them in the comments.