A few months ago I had the opportunity to have dinner with Ramit Sethi. We shot the breeze about business topics for a little while — optimizing email opt-in rates, A/B testing to victory, pricing strategies, and the like. Writing and selling software is solidly in my comfort zone and is what I usually talk about on this blog. If you want that, skip this post. We are going deep, deep into the fluffy bits!

The conversation wandered into the softer side of things: psychology, and how running businesses has changed us as people. I told Ramit a story, and he encouraged me to share it a little more widely, so here we go.

Knowing What Motivates You

Have you ever heard the expression “That really pushes my buttons”? The notion that there is a particular set of things that uniquely motivates a person has always been a very powerful one with me. I don’t always have the best handle on what I want in life, but I have enough introspection to know where my buttons are. A big one, for as long as I can remember, is labeled “Praise To Release Dopamine.” When I was growing up, I was a praise-seeking missile. I got very good grades. I got very good at getting very good grades — not because I wanted good grades for their own sake, and not out of some notion that good grades would get me something valuable in the abstract future, but mostly because I learned very early that parents, teachers, and other people I respected would say “Attaboy, Patrick” if I brought home the A.

That particular story might evoke shades of Tiger Mom parenting. That would be overstating it: I love my parents deeply, they never pushed me into anything I didn’t want to do, and we’re rather paler than most of the folks in the Tiger Mom crowd. (Though friends in high school often joked that we’re the most Asian white people they know — and seeing as how my siblings and I can together handle Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, that might not be totally off the mark.)

I realized something fairly early on, though: being a good, hardworking student and getting good grades are two very distinct skill sets. I was not a particularly “good student”, I just got particularly good at being a student. I got hooked on a lifetime love of optimizing systems when I realized that 89.5% rounds up to 90% rounds up to an A. That meant I could blow off one more homework assignment than if I didn’t understand decimal arithmetic. Math gives you superpowers.

That’s also why I got started writing. You see, after you set a multi-year expectation of always getting good grades, the praise mostly dries up. Drats! But if you particularly impress a teacher with your flair for writing, and she reads it out to the entire class, then you get to beam a little bit and you collect a story redeemable for an Attaboy at the dinner table. So I got hooked on writing. Roughly contemporaneously, I got introduced to the Internet, which if you write well and enjoy having an audience praise your ideas is like your own personal Skinner box. (If anyone ever wonders why I spend a wee bit too much time on message forums, well, there you go.)

Is there a point to that anecdote? Sort of. If you have a good handle on what really motivates you, you probably have a good handle on things which do not really motivate you. At the top of the list for me: money. Don’t get me wrong, I am fascinated by money, in the same fashion that the engineer in me is fascinated by bits and electricity and experience points and red blood cells and everything else that whirs around animating interestingly complex systems. The notion of seeking money strikes me a lot like the notion of seeking red blood cells: ewww. As long as I don’t drop dead from lack of them, honestly, I could take it or leave it. (At least qua currency. Money is also the convenient method of keeping score for optimizing businesses, which feels like a game to me. I really enjoy winning games with complicated rules sets, especially by optimizing the heck out of play, because optimization is often as much fun as actually playing the game.)

Careers as a Multi-Dimensional Preference Space

My preference set is more complicated than the above micro-sketch, but suffice it to say that I have a good handle on what I value. One would think I used that introspection to actually achieve happiness. Was I happy a few years ago? No, I was very unhappy.

There was a point in my life where I thought what I really wanted was a safe, comfortable, professional career at a big freaking megacorp. I even had the position picked out: I wanted to be the Project Manager in charge of the Japanese version of Microsoft Office. If that sounds like a curiously specific goal in life, just call me quirky: I had set about optimizing for a safe middle-class career and that looked to be the high-percentage route through the maze to the cheese. Why was I so concerned with security at the time? That’s a long story, but suffice it to say it was a combination of encouragement from my family, a culture that I was in which emphasized good grades to good college to secure employment as the thing to aspire to, and some other factors. So, true to form, I did what I thought I needed to get to that pot of goal at the end of the rainbow: got into good university, check. Studied Japanese, check. Went to Japan to perfect business Japanese, check. Got a job at a Japanese megacorp, check. Became totally miserable, check check check.

Along the way, almost totally by accident, I discovered that you could open a small software business on the Internet pretty much without asking permission from anyone. I discovered that I really, really liked almost every aspect of doing business, in the same way that I really, really did not like most aspects of working at a megacorp.

I worked for several years as a Japanese salaryman. For those of you not acquainted with the term, it basically means that a company owns you body and soul in return for guaranteeing you gainful employment and social status until you die. I was working 70 ~ 90 hour weeks for very little money doing “fun” things like translating Excel design docs into Java code and valiantly trying to fix programs delivered by an Indian outsourcing team working from design docs translated via Babelfish. Why does anyone put up with this? A lot of people, asked that question, would say “Well, that’s just the culture in Japan.”

Let’s talk about a different quirky culture for a moment: you go from a place you like being, surrounded by people you love, to a place where you do not really enjoy being, surrounded by people who you pretend to like but honestly wouldn’t choose to be friends with. You stay there for half of your waking hours, five days a week. Why does anyone put up with this? I don’t know, it’s the culture or something.

I may have said this before becoming a salaryman, but I never truly understood it: the way we work is, essentially, arbitrary. 40 hour work weeks for middling-good salaries are no more a law of nature than 90 hour workweeks for middling-poor salaries. The story we hear growing up about working hard to get into a good school so you can work hard at a good job so you can be well rewarded isn’t a lie, per se, but it is a story. A narrative. There’s a core of truth buried in it somewhere, but we don’t tell it because it is a true story, we tell it because it is a crackling good story. If you’re committed to the world being a meritocracy, that story isn’t just good, it is practically mandatory.

The world isn’t a meritocracy.

Here’s a story which we’ve all heard before:

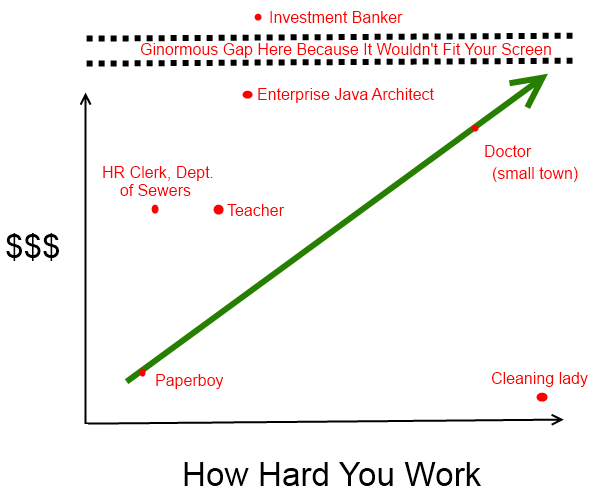

This isn’t a particularly true story. I mean, let’s start fitting some points to the line:

The graph isn’t to scale and the points don’t matter: pick your own examples if you disagree with these. The point is that “work harder and you’ll make more money” is bunk, and we know it to be bunk, and yet we tell that story anyway.

There are many, many more points that we could add to that graph: you could theoretically pick from uncounted thousands of tradeoffs on making money versus working hard. And that is with only two things under consideration! What if you considered just one more, such as “Where I want to live?” Maybe you so want to live in a particular small town in Kansas that you’re willing to accept a smaller salary. Now we have a three-dimensional preference space. The true preference space for careers has more dimensions than you can imagine, and sliced along most of them, the straight lines are a just a story.

So if we’ve got a mindbogglingly large solution space of possible jobs, some better in some areas than others, and some areas mattering more to us than others, why don’t we just we just make our mental graph just one wee bit more complex, and add in the 3,207th dimension, how happy we are with our lives if we work at that job? And then optimize for that? Heck, since the straight lines are basically not real, would that point even be a job, per-se? Running your own business is an option — and a laundromat is very, very different from selling software to elementary schoolteachers is different from building the next Google. Would it even be a point? Maybe it bobs and weaves a little bit (or quite a lot), as we find out more about ourselves, as we explore new options, and as our preference set changes over time. I cared about job security once, or at least thought I did. I honestly could not care less about what “normal” people would consider a secure job now. When we re-rate that, the points which look like good options for me change dramatically.

I’ve been an engineer, and a technical translator, and a teacher, and a paperboy. These days, I guess I’d answer to “I own a software company.” But my job, on any given day, is doing something which makes me happy. (For, again, a complex definition of “happy”, which includes things not strictly related to me, such as “Is the world better for this having been done?” and “Are the people who matter to me well taken care of if I do this?”)

Because if you’re not happy, and you’re not moving to happy, you should do something else. We should be happy.

It’s All Negotiable

I grew up in a world of simple stories with clear morals. As far as careers were concerned, straight lines abounded. Does anyone remember the day we learned that, say, a middle class man goes to work every single day, Monday through Friday, and that days not like that must be celebrations because they’re clearly the exceptions to the rule? Were we ever told that, or did it just seep in, somehow?

Here’s a radical notion, let’s try it on: never work Thursdays. Why? It has a T and an H in it — T +H = no work, that’s just the way it is, end of discussion.

Would any company ever go for that? Five years ago, I would have said that is ludicrous. Everyone works Monday through Friday. Well, OK, technically speaking university professors could schedule classes and office hours such that they never did anything on Thursday. And most of the cafes in my town are closed on Thursday. And teachers get three whole continuous months of Thursdays off. But that doesn’t matter — the rule is, you work on Thursday.

There may well be excellent reasons why people work on Thursday. Other people also work on Thursday, so that is very convenient to their company if their workers are around to answer inquiries on Thursday. But what if the company just said “Sorry customers, no service on Thursdays.” That would work much of the time — it does work, if you’re a sushi shop in Ogaki. And it wouldn’t necessarily even be the entire company. It could just be Bob. T + H = Bob isn’t there on Thursdays, deal with it.

But what company would deal with it? Isn’t it written in some book of laws or manual somewhere that Bob has to work on Thursday? Probably not. Actually, it might well be written down somewhere, but we ignore things that are written down all the time, so Thursday seems as good a thing to ignore as any. This is one of the things being a business owner has taught me: there are two parties in any negotiation, and if they agree on one particular point, then that point goes the way they agree. If Bob and the company agree that Bob doesn’t work on Thursdays, then Bob doesn’t work on Thursdays and damn what the “standard” contract says. All Bob needs is negotiating leverage to convince his company that agreeing with him on the Thursday issue is in their interests. Maybe he trades them a salary cut. Maybe he’s just the best Bob there is and putting up with his idiosyncrasies is worth having him on board. Maybe just, when push comes to shove, nobody really cares about Thursdays at all. Whatever. If Bob wants it, and asks for it, and gets it agreed to, Bob gets what he wants.

You can often get what you want.

Let’s take an example a wee bit less far-fetched than Thursdays. Let’s say you’re an engineer and you want to be able to pick your technology stack, always. You have many options here. You can found your own company, and then you use whatever technology stack appeals to you. You could consult only on the technology stacks you like. You could work for a job and just tell them “I quit if you ever put me on a project using a stack I don’t like.”

That might be considered a little disloyal, for a certain value of disloyal which occurs only in the context of a particular type of commercial relationship. Nobody expects the company to be loyal to their suppliers. The company expects you to be loyal to them, largely because it is in their interest, and they will often do a lot to convince you that their values are your values. Is this synthetic, external value really one of your values? After much consideration, I’ve come to a conclusion about company loyalty: stuff company loyalty. Companies are legal fictions which we find convenient to use to move capital around and balance accounting ledgers. I’ll save my loyalty for people. You’re welcome to your own preference set on this: stick with the company if that is more important to you than working with your favorite technology stack, but make that your choice, not somebody else’s.

Working five days a week? Your choice.

A job which doesn’t excite you? Your choice.

Money insufficient to buy whatever it is you want? Your choice.

Thinking About Money

I come from a fairly modest background, and remember distinctly that one of the perks of my first job was that I didn’t have to worry any more about buying something below $5. Then I got my first real job, and my care floor went up to $20. Then my business started doing well, and video games slid under at $60. Sometime recently I realized that trans-Pacific plane tickets were no longer an expense I needed to save for months for. So it goes.

You can imagine that if $3.50 is a meaningful amount of money to you, you lead a fairly frugal existence. I used to live like a monk, and I even idealized that a little bit, but I’ve come to realize that not-spending-money is not something I particularly value one way or another. Back when my business had no budget, I would gladly do web designs by myself, even though I don’t particularly enjoy it and I am not particularly good at it. These days, the business is doing rather well, so if I need a web design done I’ll just pay someone who is good at it and likes it, and I’ll get back to doing more important things like strategizing or doing marketing or maybe reading a supernatural romance. (internal monologue: “But Patrick, you’re not allowed to read in the middle of the day! … Oh wait, I guess I am.”)

For a business, money is a tool to get things that you want. That started creeping into my personal life as well. Consider my apartment move in February. I could have spent a week boxing things up and cleaning my apartment. Or, I could have paid $2,000 and gotten people to do it for me. Earlier in my life I would have thought $2,000 is an incredible amount of money (almost a month’s salary!) and that there was something vaguely lazy about not doing the work myself. The businessman in me made the fairly simple calculation that I could pay the movers $2,000 and get back to charging customers something rather more, and I would not be exhausted and bored at the end of the day. Here is the money, gentlemen, I’ll be programming at the cafe if you need me.

Confidence Issues

I have longstanding confidence issues. I often feel like maybe I’m just getting praised for playing the game really well as opposed to demonstrating actual merit. (I have since found that many, many people I respect likewise worry they’re faking it. Anybody in my audience got the same issue? If so, and if you respect me, there you go — you’re not alone on this one.)

I have found that actually showing confidence issues, on the other hand, does not do great things for one’s business. For example, let’s say you’re doing pricing for a product or service your offering — maybe your software, maybe your labor, whatever. If you have confidence issues, you will undercut your own negotiating position by underpricing. Been there, done that, got the T-shirt.

I do consulting, on occasion, and it makes up most of my income and rather little of my day these days. Consulting is a topic for it’s own post some other week, since I learned by a combination of mentorship and making expensive mistakes and would love to save other folks with less access to good mentors some pain.

At some point in discussing a consulting engagement, you have to quote a price to the client and get them to say “Yes.” You could write entire books about the psychology of that fifteen seconds, but in a nutshell, you don’t want it to cause you to think “Oh my goodness I’m not really good at this and charging any money is basically stealing so maybe I’ll give them a discount to my lowball offer and then work extra hours to make up for how terrible I’m being right now.”

I got clued into consulting by Thomas Ptacek at Matasano, who has gone from Internet buddy to client to personal friend. It’s a funny story: I spend too much time on Hacker News, he spends too much time on Hacker News, we both had reason to be in Chicago, so I suggested we get coffee and talk about… whatever message board geeks talk about when they get coffee, I don’t know. He was very receptive to the idea, so back in December 2009 we grabbed a coffee and went back to his office to drink it. He then locked me in his conference room for three hours and proceeded to interrogate me with one of his co-workers about everything I knew about SEO and marketing. It was, seriously, the most fun I had all year. (Remember, praise-seeking missile. That entire situation was basically pure brain crack for me and I was getting a free drink out of the deal.)

At the end of the discussion, Thomas mentioned that, if I had phrased my invitation as “Why don’t I consult for you” rather than “Why don’t we grab coffee”, he would have gladly written me a check. I had a vague idea that a semi-decent engineer (my mental positioning for myself at the time) was worth about $100 an hour, and mentioned that $300 didn’t seem to be enough money for either of us to worry about. He told me that he would have paid $15,000, and it blew my mind. (There was a bit of discussion on that point — his coworker thought that to justify $15,000 they’d really need a written report, but the petty cash drawer could have maybe swung $5,000 for it — and my mind got blown again.)

I would like to say that after starting consulting I went immediately to charging $5,000 an hour, but sadly for my bank balance, not so much. I distinctly remember the first time I quoted someone, though, over email. I typed a number, agonized over it for ten minutes, then typed a number 50% higher, then curled up in the fetal position for a few minutes, then impulsively hit Send and started hyperventilating. Ten minutes later I got an email back and, to my enduring surprise, they did not hate my guts for picking that number that was 50% bigger than a number I was already barely comfortable with.

Since then, I’m gradually getting better at the confidence thing. Partially, it is as a result of trying new things for me and realizing that, no matter how intimidating they were when I started, I largely don’t end up dead. Consulting engagements go well. When a new client asks what my rates are, I pick a bigger number. They’re generally OK with it. If not, oh well, it turns out there are often many ways to negotiate such that we’re mutually happy. (Including me just letting them go. I mean, I don’t need to work everyday.)

Speaking of confidence, sending email to people used to be a bit of a hurdle for me. Even asking Thomas out was on the edge of my comfort zone. After trying it many times since then, and observing the behavior of other people in business who I admire, I have come to realize that it is not a big deal. (Relatedly, almost nothing is as big a deal as we think it is.) This comes up over and over for young engineering-types on Hacker News so, if you get one actionable piece of advice out of this, get comfortable with sending email to people and asking them to give you what you want. This will virtually never cause a mortal catastrophe. I still have a ways to go to do it routinely, but it gets easier every time I do it. Definitely explain to them why giving you what you want is in their interest, but ask. They might say “Not interested”, or they might not reply, but they’ll very rarely put a contract out on your head.

Can Your Job Change Who You Are?

After you have asked a CEO or two to coffee and not gotten your hand bitten off, you would be amazed how less scary “Say, why don’t we have dinner together two weeks from now?” is. That could, possibly, have been the most important sentence of my life to date. She didn’t put a contract on me, either.

(I generally keep my work life and personal life fairly compartmentalized, so I won’t talk too much about that, but a funny anecdote: we were talking about money one day and future career plans. She told me she’d continue working at an office job which she doesn’t particularly enjoy so that we’d have enough money to support a family. I was confused for a few seconds and then started laughing: I had shared less with my girlfriend about my finances than I routinely publish on the Internet.)

And if you’re getting comfortable with addressing folks as your equal and reaching mutually acceptable solutions, why ever stop?

I have to deal with city hall from time to time. I used to be very timid about it, afraid that I was wasting their time or about to step on a bureaucratic landmine. These days, they’re a service provider and I’m a customer — a customer with limited options for changing providers, granted, but a customer. CEOs get what they want. When I go to city hall, I put on my suit, slide into professional mode, and get things accomplished. They can’t do something? Of course they can, or they can find someone else to do it, or there is a particular fact which they need from me to justify doing it, or maybe I’m just asking the wrong way and I should try again. And I don’t have to be intimidated or embarrassed about doing this — it’s just a negotiation, and not even a really important one, at that. Plus, if worse comes to worse, I could always just send a lawyer to do it.

I missed a flight a month ago, and got one sentence of a very stern dressing-down from the clerk at the Delta counter. Years ago, that would have paralyzed me. I was totally unphased: my brain immediately supplied “They likely sold the seat to someone on standby and, if not, Delta’s revenue maximization is not your moral imperative. You paid them for a service. The price of your ticket and standard social graces is the maximum extent of your obligation to them.” I immediately cut in with “Sorry for the inconvenience ma’am, these things happen. What are our options?” (It turns out that if you fly ~100,000 miles a year, your options include them putting you on the next flight, for free, and getting a discount on your hotel room that evening.)

My friends also tell me that I’m almost a different man these days than even two years ago. The most striking quote to me, from my best friend: “You look… healthy.” Apparently the old day job was beating me down so thoroughly that I looked about as bad as I felt, and even on those days when I wasn’t dog tired I walked with a bit of a stoop. These days, I even stand straighter. I think that is almost too convenient to be true, but hey, it’s a story.

This Actually Can Matter

If you don’t have a good handle on what you want, or even worse, you don’t actually consult it, you could make decisions which are not really in your interests.

I have been somewhat seriously kicking around the idea of taking investment recently. Thankfully, at Microconf, I got the chance to bounce some ideas off some smart people, including Hiten Shah. He asked a very perceptive question: why did I want to take investment? And honestly, I didn’t have a really good answer for that.

“I have the ‘ran a small business’ merit badge already, and am looking for new challenges.”

“Is 10x-ing your business a challenge?”

“Yeah.”

“Do you need investment to do it?”

“Nope, I have done it before. Besides, even 10x-ing it wouldn’t produce a favorable outcome for most investors.”

“Then why not skip investing and continue doing what you love?”

“…”

The business is growing quickly. I’m bringing someone on in August. My life is better than it has ever been. Taking investment would commit myself to a few years of a very different trajectory, including some things that I have no reason to assume I would enjoy, like managing employees, getting involved with intrapersonal conflicts, and having to give up ownership (not the equity, the responsibility) of parts of the business that I genuinely enjoy to focus on CEO-ing. In return, yeah, I guess you get a quirky kind of social status and a shot at getting a lot of money, but if I had so much money that a dragon would be embarassed sleeping on it, very little about my life would change.

I’m pretty happy with where I am. Today rocked. Bring on tomorrow.